Silent theatre punches through sound barrier

Originally published in Gulf Times on April 22, 2008

THE stage is set and actors are playing out their roles. The audience - initially doubtful - is fully immersed and fascinated by the act which has no score or vocals. This is Silent Theatre, all the performers are deaf.

The theatre set up three years ago, was the brainchild of the Uganda National Association of the Deaf (UNAD), and has now gone international, winning several awards on the way.

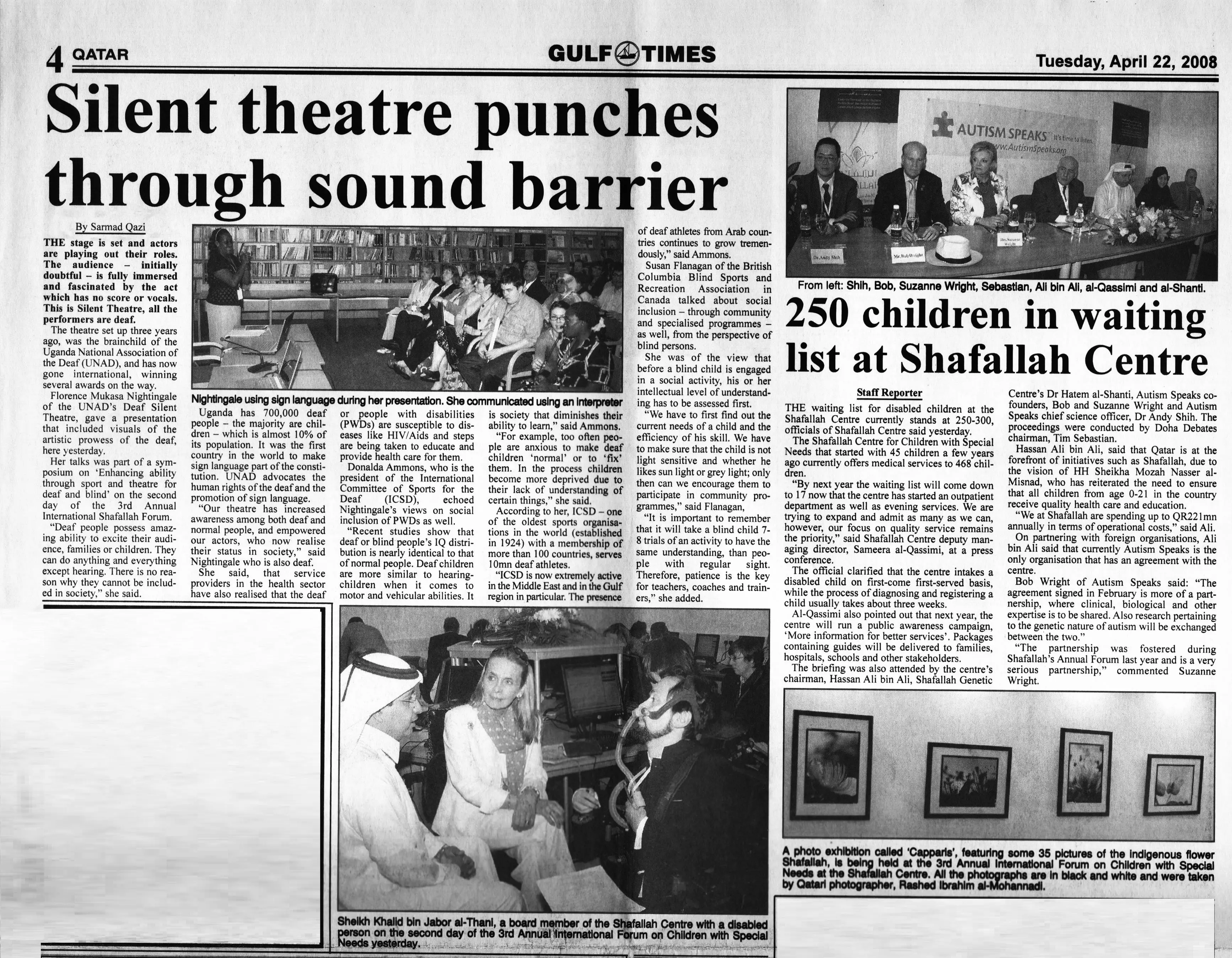

Florence Mukasa Nightingale of the UNAD’s Deaf Silent Theatre, gave a presentation that included visuals of the artistic prowess of the deaf, here yesterday.

Her talks was part of a symposium on “Enhancing ability through sport and theatre for deaf and blind” on the second day of the 3rd Annual International Shafallah Forum.

“Deaf people possess amazing ability to excite their audience, families or children. They can do anything and everything except hearing. There is no reason why they cannot be included in society,” she said.

Uganda has 700,000 deaf people - the majority are children - which is almost 10% of the population. It was the first country in the world to make sign language part of the constitution. UNAD advocates the human rights of the deaf and the promotion of sign language.

“Our theatre has increased awareness among both deaf and normal people, and empowered our actors, who now realise their status in society,” said Nightingale who is also deaf.

She said, that service providers in the health sector have also realised that the deaf or people with disabilities (PWDs) are susceptible to diseases like HIV/Aids and steps are being taken to educate and provide health care for them.

Donaida Ammons, who is the president of the International Committee of Sports for the Deaf (ICSD), echoed Nightingale’s views on social inclusion of PWDs as well.

“Recent studies show that deaf or blind people’s IQ distribution is nearly identical to that of normal people. Deaf children are more similar to hearing-children when it comes to motor and vehicular abilities. It is society that diminishes their ability to learn,” said Ammons.

“For example, too often people are anxious to make deaf children ‘normal’ or to ‘fix’ them. In the process children become more deprived due to their lack of understanding of certain things,” she said.

According to her, ICSD - one of the oldest sports organisations in the world (established in 1924) with a membership of more than 100 countries, serves 10mn deaf athletes.

“ICSD is now extremely active in the Middle East and in the Gulf region in particular. The presence of deaf athletes from Arab countries continues to grow tremendously,” said Ammons.

Susan Flanagan of the British Columbia Blind Sports and Recreation Association in Canada talked about social inclusion - through community and specialised programmes - as well, from the perspective of blind persons.

She was of the view that before a blind child is engaged in a social activity, his or her intellectual level of understanding has to be assessed first.

“We have to first find out the current needs of a child and the efficiency of his skill. We have to make sure that the child is not light sensitive and whether he likes sun light or grey light; only then can we encourage them to participate in community programmes,” said Flanagan,

“It is important to remember that it will take a blind child 7 to 8 trials of an activity to have the same understanding, than people with regular sight. Therefore, patience is the key for teachers, coaches and trainers,” she added.

As Published